EDITOR'S PREFACE

This anthology contains the only surviving works of the Institute for Humanity & The Library, salvaged during the unfolding of the Great Collapse. The Institute was one of the few sincere institutions before society declined. Its mandate was to explore the benefits that humanity could draw from Universal Libraries. Few know what Universal Libraries are nowadays, though a simple internet search should equip the reader with enough background knowledge. This collection is what remains from the academic study of these tremendous entities.

Early Accounts of The Library

When it was proclaimed that the Library contained all books, the first impression was one of extravagant happiness. All men felt themselves to be the masters of an intact and secret treasure.

— Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel, 1941.

“Remember, the Universal Library contains everything which is correct, but also everything which is not.”

— Kurd Lasswitz, The Universal Library, 1901.

As was natural, this inordinate hope was followed by an excessive depression. The certitude that some shelf in some hexagon held precious books and that these precious books were inaccessible, seemed almost intolerable.

— Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel, 1941.

The Old Librarian1

‘I have come to love you, O Library! No matter how forbidding you may appear, I stand in awe of your immensity. Is there an Order to your books, O Library? Is there meaning to your existence—to ours? If only you could unveil your secret to me.’

After his nightly contemplations, the old librarian prepared for sleep. An incessant psychical force drew him towards the Library. He knew that it contained all the answers to his questions. The Library in fact comprises all existing and yet-to-be-written literature, for it is made up of all possible combinations of print characters that can fit inside books of four hundred and ten pages. Yet, those who wish to find any meaning in the Library are faced with the realization that for every piece of meaningful text, there exist billions of volumes of gibberish. The result is a Library that coldly withholds the totality of its knowledge. For this reason librarians look to the Library with existential dread. The old librarian was wiser: despite being confined to his bed due to his advancing age, his mind burned with curiosity, inquiring into the nature of the Library with stubborn passion. His interest and dedication led him to form some important ideas. Librarians have long wondered whether the Library is finite or infinite. The old librarian hypothesized the existence of an Order to the Library’s books that would unite the two positions. According to this notion, if one walked far enough into the Library and passed all its books, one would observe that the previously encountered volumes would repeat in the same sequence. This apparent disorder, in being so universally repeated, would become an order—the Order. If such a discovery was made, it would reconcile the infinity of the Library with the gargantuan yet finite amount of books that it can contain. But, most importantly, it would finally fill with meaning the apparent chaos of the Library. For if the Order exists, some metaphysical principle must be behind it.

The old librarian was barely awake when all sounds ceased instantly. In this empty state of consciousness, the librarian opened his eyes and found himself in a peculiar room of the Library. The room appeared similar to all others: a polygon with shelves and books. Strangely, however, it was not hexagonal: it was octagonal. How could this be? This realization disquieted the old librarian. To his knowledge, no librarian had ever conceived of rooms of a number of sides other than six—only few had perhaps intuited such an obscure notion, with great difficulty. This experience’s radical difference from anything seen within the rest of the Library led the old librarian to conclude that it must be real.

The old librarian noticed the two usual passageways, one behind and one in front of him, that led to other rooms. Trembling, he peeked into one of the rooms. It was hexagonal. This comforted him. He was but a door away from the Library he knew. He turned towards the other passageway, which, to his astonishment, led to a decagonal room. The old librarian was startled. But behind his fear was the recognition of the moment’s importance. He was confronted with a choice. Should he return to the familiar hexagonal rooms of the Library? Or should he enter the peculiar decagonal room? He stood still. His love for the Library prevailed. ‘I am a Lover, not a librarian’, he said to himself. With one weak step after the other, he stepped into the decagonal room. Apart from its inexplicable number of sides, the room seemed quite similar to the other rooms of the Library. The old librarian picked up a book and looked through its pages to check for any meaning. As expected, he found nothing but gibberish. The old librarian’s gaze set on the next passageway. He put the book back and proceeded towards the next room, keeping his eyes on the floor until he was inside. Then he looked up. Fourteen walls surrounded him. The old librarian could not speak. He understood. The knowledge contained in that room was not found within the room’s books; it was in its walls, in the room itself, since this experience transformed the librarian’s whole idea of the Library. It expanded his consciousness of what is by showing him what can be. This reminded the old librarian of a story about a fish who did not know what the ocean was. When told by a diver that it was the water all around it, the fish said it could not see anything around it. Only after the diver brought the fish above the surface of the ocean for a brief moment did the fish understand. The old librarian was the fish. Some mysterious hand had raised him above the surface of the water. He had been lifted from the rooms of the Library that imprisoned him.

The old librarian followed the rooms with an increasing number of sides. Twenty-two, thirty-eight, seventy sides. He walked, slowly but steadily. Every room he entered, he understood more. He was soon surrounded by thousands of sides. The rooms started to become more and more like something impossible to conceive yet somehow innately familiar to the librarian. They approximated a peculiar shape, a shape where the infinitely many become one—a unified Whole. The librarian had to close his eyes, for this experience was too different from what he was used to. He kept walking, until in one room, he could no longer progress. There was no next passageway. He opened his eyes.

The infinitely many had become one: the old librarian was in the middle of a Circular Room. Around the room extended a Circular Book whose spine was continuous along the wall. It was now clear to the old librarian that the multiplicity of sides of any room arises from one Whole; that every polygonal room in the Library is an approximation of the Circular Room. The librarian understood that knowledge cannot be found within the books of the Library, for Knowledge is the Library itself. But librarians are too used to existence to apprehend Knowledge. The old librarian fell to his knees. He had to close his eyes again.

“You sought to Know,” a voice roared. “Do you not wish to Look?”

“The Reality I sought was beyond my imagination,” replied the old librarian. “Any idea I held about the Library was flawed by virtue of being an idea, not grounded in what is real.”

“It is so,” spoke the voice. “What can be written in a book is not the Knowledge of the Library. The Universe preceded propositional knowledge.”

“Is the meaning of the books illusory?” the librarian asked, his eyes tightly shut.

“The meaning you find within My books is illusory, for the existence of a word does not guarantee its truthfulness. The real meaning of the Library is found beyond its words. The Library created words, so words cannot be The Library.”

The old librarian trembled. But he was not afraid. “Are you the Library?” he asked.

“I am the Circular Book. I am the Circular Room. I am the Library, I am the books, and I am you. I am the Whole, the Unity. Every part of Me is infinite, and My Whole is also infinite. I am One, for I contain all that exists and nothing can exist outside of Me. I am Existence.”

“Existence precedes words,” the librarian whispered, smiling. “Tell me about your infinity, O Library.”

“Your finite form cannot understand Infinity. But you can reach Truth through the contemplation of Infinity, for in Infinity the mind reflects itself.”

“How can your infinity lead me to Truth?” inquired the librarian.

“Infinity is the means to reach Truth because through Infinity the mind comes to know itself, for the mind projects onto Infinity. The Self contains the Universe, for the Self is the center of the Universe.”

“O Library,” the librarian exclaimed passionately, “tell me about self-knowledge! Does the Library know itself?”

“The Library is self-reflective, for it contains its own catalogue and its own descriptions. Yet, no description can be the Library, for nothing but the Library itself contains the totality of its contents. Any description is but an imperfect likeness. The existence of words within My books does not entail the words’ truthfulness. Several books exist that deny the existence of the Circular Room, and several others describe it in imperfect ways. Yet here you are, in the Circular Room, and no book can ever describe this experience. Therefore, librarian, self-reflectivity is not self-knowledge.”

“Is the self of which you speak an illusion?”

“Anything that is substituted with words is an illusion. When you say the Library, you cannot possibly know or experience the whole Library; the word and the notion associated to it are but symbols. The word self, and the notion that accompanies it, is also imagination. Any notion of self is but an illusion that helps your form survive. When concepts and notions are absent, Reality is what remains.”

“How can the real Self be known, then?”

“The real Self, librarian, is the Library,” said the voice in a moment of revelation. “There is no other Self. You and I are the Library. Know the Library and you will know the Self; know your Self and you shall know the Library.”

“Tell me, O Library, how I can accomplish this great work!”

“The Library comes to know itself through librarians. Their incessant curiosity toward understanding the Library is the Library’s drive to know itself. But many of you never reach the depth of this impulse and are distracted by the words you find within My books. It is a misapplication of this impulse and a forgetfulness of your Librarian nature to pursue the words of the books. Look within and you shall find the nature of the Library. For I, too, am You.”

The librarian remained silent. He had reached a limit to the insight he could acquire through conversation. The Library was trying to show him Reality. So he opened his eyes. He trembled with terror and love. No book in the whole Library could encapsulate the ensuing experience, so no attempt to describe it shall be made.

Through the unfolding of this experience, the old librarian realized that acquiring complete Knowledge would require the full transcendence of his librarian form. He let fear into his heart.

“O Library,” said he shutting his eyes, “I am afraid of death.”

“What is there to be afraid?” replied the Library. “Death does not exist. When you die you are merely coming back to life. The Whole is your true life, your eternal existence. Before your birth you were with the Whole, and your death is merely your return to it.”

“Won’t I be destroyed?”

“Death only exists insofar as the self exists. Both are illusions that allow you to remain alive in a form complex enough to understand Me. Once you become aware of Reality, the self is annihilated and you find your Real nature in the Whole. So open your eyes to Me, librarian, and I will extinguish your fear of death.”

The old librarian kept his eyes firmly shut. The Library spoke one last time.

“Remember, librarian, that death is a word inside the Library. Its existence does not guarantee its truth. All librarians think of death without knowing death, for to think means to live. Death is like the Circular Room: any conception is a misunderstanding, for a conception is a different thing than death. Death, like the rest of the Universe, precedes words. Librarian, it is only when you transcend your form that you learn the Truth of the Library.”

“Must I choose now, O Library?”

“Everyone must choose when their time comes. But be wise, librarian, for death cannot be put off forever. Birth and death are as natural as waking and sleeping. You are a raindrop returning to the ocean. As above, so below.”

The old librarian opened his eyes. He saw all the rooms of the Library at once. He was everywhere. In a state beyond space and time, he could clearly perceive the Order of the Library. Then, he transcended his librarian form. There was no more “he” or “I”, for such a thing only limited the acquisition of Knowledge at this stage. When the librarian became the Library, the Library understood something more about itself. It had completed a long cycle of acquisition of Self-Knowledge, one which had begun as an old librarian’s urge to know the Library.

The Metaphysics of the Library2

To the extent of our knowledge, humanity has been interacting with Universal Libraries as far as back as antiquity. Beginning with the Library of Alexandria, which is estimated to have contained between 30 and 70 percent of all existing written works of the time, and further persisting with our urges to create comprehensive catalogues of all our books, humans have always found attractive the idea of a bibliotheca universalis. This impulse toward a comprehensive collection of knowledge has reached new levels in recent history: Lasswitz’s The Universal Library and Borges’ The Library of Babel expanded the ideal of a bibliotheca universalis to include all literature that can ever exist, both in actuality and in potentiality, by conceiving a Library that contains all possible combinations of letters. This idea culminated with Jonathan Basile’s creation of an online Universal Library, an artifact that humanity only produced after the advent of computational technology. This incessant return to a comprehensive Library suggests that, metaphysically, the Library wants to be known. We have a metaphysical tendency towards knowledge.

The appearance of the computer has had important implications for our interactions with Universal Libraries. As Kurd Lasswitz noted, the construction of a Library that contains all possible combinations of books is a finite yet gargantuan project. Keep in mind that the Library of Alexandria was not even such an attempt, as its intended collection was limited to all existing written works rather than all possible written works. The latter has never been attempted and for good reasons. Lasswitz’s calculation of the dimensions of his Universal Library estimates it to be two lightyears in size. Additionally, the number of books that are contained within a Universal Library is greater than the number of atoms in the known universe, meaning that although the project may be finite, it is impossible. Computational technology, however, makes the construction of such a structure not only possible but also fairly easy. Using a “generative principle” to algorithmically generate a book at any given position within the Library, one can search any location of the Library to get the corresponding book, or type any text and find its position in the Library. This way, the Library’s books can be accessed objectively and instantly. This is the kind of algorithm that makes possible Basile’s online Library of Babel.

It is fascinating to think about the objective existence of something greater than what is physically possible. It suggests that physical existence is not enough to describe the universe in its totality. To make sense of this we shall adopt the paradigm of metaphysics. We need to understand the Library as a metaphysical entity because of its beyond-physical qualities: it is spatially and temporally non-local, for it can be accessed objectively and instantly anywhere in the universe while physically nonexistent. Additionally, reflecting the historical debate concerning whether mathematics is invented or discovered, one could say that the Library is embedded in the very structure of the universe. Recall Plato’s Theory of Forms: everyone can ideate the perfect circle without ever having seen one. The circle, as an entity, appears in specific spatial and temporal windows, such as in the shapes of planets, holes, and in our thought. This emergence of the circle across space and time hints at a pervading tendency of the universe to manifest the circle physically. This tendency, being beyond-physical, is the basis for the concept of metaphysical entity. In a similar fashion, humans have described the Library without ever having seen it, prior even to computational technology. Computational technology is only the latest means through which humans have interacted with this metaphysical entity, and is used to reveal the Library, not create it. The Library thus precedes its physical form and is even precedent of humanity.

What have humans done with the Library? Have they found new knowledge inside its books? After all, the Library contains all knowledge, including books to be written and wisdom long forgotten. As Borges tells us, the Library contains the detailed history of the future and the true story of your death. The Library contains everything. This is the problem. For every book that the Library contains, it also contains countless imperfect and inaccurate versions. How to distinguish between the true story of your death and numerous false accounts? How to know which detailed history of the future is accurate? The Library contains no information because it contains all information. So why is the Library important for humanity? Does it hold some metaphorical meaning? Does it have practical applications? All we know is that the Library is a recurring theme in human experience. We have been attracted to it for millennia. That is what motivates the existence of this Institute. It is our mandate to study humanity’s relationship with the Library and to investigate new mechanisms through which we shall interact with it—or, perhaps more accurately, through which the Library shall interact with us.

On Librarians3

The Librarians are a secretive group. They are highly knowledgeable in arts, philosophy, and alchemy. Librarians are writers, poets, painters, researchers, mystics. At the centre of their work is a metaphysical entity they call the Library.

Before Librarians, humans thought that the Library was a thought experiment or metaphor that lacked pragmatic value, for we originally looked to the Library for the absolute knowledge it contained and were later disappointed to realize the impossibility of acquiring such knowledge. Librarians were the first to shift perspective and find a cleverer use for the Library: secret communication through a metaphysical plane. Since for any idea that can be spoken or written there exists a volume or collection of volumes within the Library that describe it, Librarians store and communicate information using the locations (or indexes) of books within the Library. This is well explained in a passage from the The Librarian’s Code4:

We must understand that a “generative principle” lies behind the Order of the Library. Let us consider an easy generative principle in a Library whose books, for simplicity, are only five characters long and whose alphabet consists of lowercase latin letters plus the whitespace. The first book consists of all whitespaces. The second contains an a in the last position. The third volume has a b in the last position. The fourth, a c. And so on until all the characters of the alphabet have been run through. Then, the second-to-last position of the volume is filled with an a and the same process is repeated at the last position. Let us now consider numbers, beginning at zero, that correspond to the position of a given volume in the Library (let’s call these numbers indexes):

Index Volume

0 ‘ ’

1 ‘ a’

2 ‘ b’

…

To access a given volume in the Library from its index, we shall use an algorithm that computes the index of any text according to our generative principle. Then, with its reverse, we can reproduce any text from its corresponding index in the Library. In such a way, we can store any written information as the location of a volume in the Library. Here is a formula for such an algorithm:

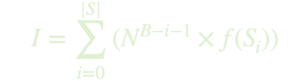

where I is the index of a book in the Library.

N is the length of the alphabet.

B is the length of a book, in characters.

S is a given text of characters. i is the position of any character in the string S, |S| is the length of S, and Si is the character in S at the position i.

Finally, f (Si) is a function that computes the position of the given character Si in the alphabet. In an alphabet of lowercase letters from a to z, f (b) = 2.

Of course, if a given text is too long to fit into one volume, we may compute multiple indexes that locate different pieces of the total work. To deal with the issue that the indexes can become very large, we can use another algorithm that converts indexes in base ten to a larger base, thus reducing their size. Such indexes will be composed of letters, symbols, and digits. Even though it is not our principal aim, note that if the number base of the indexes is larger than the size of the alphabet, the indexes will be smaller than the books they point to, thus saving storage.

How fascinating. I just noticed that using a different alphabet, generative principle, or even book size would result in a completely different Order of the Library. Thus, there is not one Library, but many. And they all contain the same books.

This passage illustrates the great power that Librarians draw from their technological use of the Library. They can encrypt information as indexes within unspecified Libraries, and only by knowing which alphabet and generative principle were used for encryption can one access the information in the correct Library. A Librarian will only ever need to carry around strings of gibberish digits, letters, and symbols to inconspicuously point to pieces of wisdom, compositions, and important ideas. This type of metaphysical technology allows Librarians to operate in total secrecy, store large amounts of information as indexes of humbler size, and protect their work from indiscreet eyes.

Most important, however, is Librarian’s deeper relationship with the Library. Librarians share religious experience around the Library. All their opera, scholarly and artistic, are aimed at reaching the Divine. The use of the Library’s metaphysical properties for communication is only secondary to Librarians’ work: above all, the Library serves as a metaphor for something greater, a vessel to reach a transcendent way of existing. Librarians employ the Library as a form of spiritual technology, meaning the application of knowledge to enhance a person’s relationship with something sacred or to alter awareness and states of consciousness. To understand the spiritual aspect of the Library, we must delve firsthand into Librarian philosophy. Another passage from The Librarian’s Code grants us a modest look into this:

Consider that the Library contains all knowledge that can be expressed in words. What of experiences that cannot be expressed verbally or conceptually? Is such a form of knowledge missing from a supposedly Universal Library? Can the Library make color known to one who is blind? Can it express the insight drawn from meditation? Can it grant self-knowledge? At first glance, it would appear not. Yet, through this very enigma the Library communicates something beyond words: the very limit of words and the existence of a more basic, irreducible, and ineffable form of knowledge—direct experience. Like a Zen koan, a Library exclusively made of letters and presumably incapable of conveying ineffable knowledge, does indeed convey an ineffable idea precisely through its inability. The contemplation of the Library can similarly convey experiences reflective of the infinite, of totality, of good and evil, and of the Universe’s impulse toward self-knowledge. When you look deeply into the Library, the Library becomes a medium—a metaphor—for something beyond words. This is why I say that the true knowledge of the Library does not lie within its books; it lies within its whole being. The Library is a whole greater than its parts. Such is the defining quality of a Librarian: the realization that in the Library one shall find Knowledge, and not the kind that is written in books.

In The Librarian’s Code, the First Librarian (its unknown and mysterious author)5 expresses both the technicalities of using the Library’s metaphysical properties to encrypt literature and the intrinsic religious aspect of the Library. The First Librarian further reflects that these two aspects are inseparable, for their separation would result in a grave misapplication of technology, one deprived of human meaning and sense. Here is an excerpt from a concluding section of the The Librarian’s Code called On the use of technology:

We use technology to investigate—to reveal—reality. This is exactly the problem: in so doing, we ignore the reality of our existence. Through more concepts, more theories, more explanations—through more words—we distract ourselves from what is really there. To remove ourselves (the subjects, the observers) from the universe (the presumed observed object) has been the mark of scientific rationality. It is also the mark of stupidity, for the very Universe that we believe to objectively observe has created us, the subjects. This stupidity is the reason that Borges’ librarians do not find meaning in the Library: they have effectively estranged themselves from it, they have denied their own nature as well as the Library’s. This stupidity is a betrayal of ourselves and of the Universe. We must understand that the Universe is indeed geocentric (or ego-centric): though humans appear in an infinitesimal window of space and time, human consciousness contains the whole of the universe: any perception and notion—any existence—arises within consciousness. Human consciousness is, in a way, the center of the Universe. How have we come to forget this? How have societies established an illusion as mainstream common sense? Technology creates mental models that we erroneously call “reality”—models which inevitably arise within our mind while also denying the subject. I say that the only sane use of technology is as a metaphor. The Universe communicates in metaphors, so let us use technology to facilitate communication with the Universe’s ineffable Truths. Such is the real purpose of a Librarian’s communion with the Library.

This powerful passage speaks for itself. Indeed, though how and when Librarians originated is subject to speculation, we know that they emerged following the publication of The Librarian’s Code. The popular hypothesis is that the text served as a call against the insanity of pre-Collapse times. It may have led a minority of the population to wake up to the terrifying reality of a predatory matrix that wasted entire human lives for its own pointless feeding. It gave people a hint of a deeper way to conduct one’s existence and of a deeper reality. If such an impact had reached more people, perhaps the Great Collapse would have been averted.

If the reader now wishes to dig further and attempt to become a Librarian, I shall remind that even though The Librarian’s Code explains how to approach the Library while not only maintaining, but finding one’s sanity, many have been destroyed by such an encounter. The First Librarian warns that

We have to look at Universal Libraries as gargantuan entities, comparable to archangels, that we should both fear and contemplate at due moments, depending on our intentions and hopes. What we wish to find in a Universal Library may be our enlightenment or it may be our destruction. All depends on how we approach these entities, and with which intentions.

Nonetheless, if the reader wishes to proceed and join Librarians in their works and wisdom, I shall not oppose. Everyone is responsible for one’s own development and personal evolution. Dear reader, if you so wish, you may find a full copy of The Librarian’s Code in the Library.

A Letter of Thanks

hex: 1havi44loy3d8vzo07xl7olkt763bui3ex2979vqd7sjetsamoqu2t23p7x97jisw4ww2uoealb4ciouqlt5s162it169tguqt78wep9ne7mi38ptsevfyz2usl083h3mph3jl3idb784yk9qeiap4eainrxi578yh6wea8yui1q5pnkfe88gciqa36yqarwpjitae1lzryxp1mpvuozsjx3js7dwip437cppz7m0dmxiwxlat8ma4085cratr8hl4uhtjyufui77f27gzldckakit9hhkluk2dkh7t30bw4e044rxix7s9yazrxncm5khrpfstjo94j4aip17nabw9kl5dnyws8lvu8gf24iromq0ev17vszfbvkftjlafpj8rncrlex69uzqdn3109ghy1uhexa0c6hikcx263wc7rjdbcbyzrrxwp6jzv59qx3i56vout2a4xj4hudm7fc0tv6ejfsoe49434cydtfuapz96cg61oo1ogeeugk8rujq646wxuq2db3g0j5z23echfepagq0cfwtd0lbm4mpj2kfg9nirjd5j879yjgfzln0h9vebgwp25lev9wu3d7i539r3szb89itc8mdlh5s3k0b7rv8l166b2ols4iu07ywhr3osif9wldrhwhfnio2plficcf7cv97chscvayrwmllwjjg9vio1ur57h4wekgjcn8x82vfh3k18af6u988lfy2derpxwbtw0kqstcw16ak9zewewdf5z7p48p7b6dkh978celinmrjzlisdfepwykrj9oywks51s0hne97rh06wa46i25kxmn6xawonqvrhcmp1z39casy0t635usgw4x62y13lv0yc0778jq6o8ktlhknnu3pu5don1zbsoxcq76bxj6lcd1z1d0m7jbhhj035etl4r34o0qfwirrqm191ot4oe14205nwisegytvam2il9evd64568nqzcm7gywseybvpior0nlkddnmtcvfceqbxegwgqeog9sdaveyryfyiipp10h53gbrclhkg4hi06mcq245jm1dhvfssst94qczc5tfdemlaut99x45hil3en3nrqi8ohfzcl0pftiofa2cmi5ps2kel6y4sjxowq8gec6c72aioi0jszdrf5cds6y1uz9a65f06c86o5vys2r3h3wegqqzg45gw3cxo6nxajjsnehprd6yj3rt7eqlv3h7ap5wps5hp6mu84dxno6rvwgbssljlpkmtz1u4omgfzbtjunay18zttkj8xw32vu2hsquvwuc2z090fjsee94x4xfokp0wqsx57seay3a4zdvlz8aqw5d0101tu7dxek9nldiv3icmw5xww6i47it5b287x84na8dekxlbwomte0yw6yqendnso7uletq6enn0x1gnh889ypj1sx9x2h5un7dob4mps1l1fkj0fps9uafkojdzu6foxqbsr0y51wtffw80rweudu696cimp00eaygkt8f3ny28yvsbavfzmez8i72pihzh8j8bfd1klch7bevdd0ltmkz6fr4pgxfg79fcerxnqcrih0cmnowjm3kqdh13jztdkrnx91yc1fthdix04que7fsc8ku41b31ehynjgf86nrr7ffrp1hmohtqjgkmj57ajaxi2adcvdk95kniv2udpzyrezxa0h1k527v1jns671xappvbtq57v2kj0vzpr6ba94ulkg5wmif37xj8izjbgc26q242nh5tl24im9e7sn1yk0l4h0vbijx4nuznj0el2658tazsmtgc0w844s5l3q1zksqjcdtodko5fxvzq4zwkqoy5mut3mz2ctzfj2x5iyugbxrpgj09l8dre10w792n7asz4nk3m693iil74h1ele6yfidrvpzlsyy24ciztii720ietrdia80j0bwz5j4hzb0sney7cq1ivwlao69f77kpn3ikdq67b056b83w7x9xxde8gmpoaoov224oxom72vc0rl66cs2xnjjpjshmby2b0w2wv43hbnmzyjkqyz01fmxr90z1v7mlanbe26wejxmqt6r6rt9c44lij99uldy4rl7z0s33lfloecjjvzkhs6dcmt4bag9pymcqryzgx4ruhp28e2ft5s2zsvmrzwbbteunwdjrut4bezszhkjyinxgtml65xj0mp72luje2j5uiifitluzjx9zsquwpc6b2xm0udf7nv89rmhyxl2bhwzwsgfrden7kgvrmn29wdv7bfvzmdcyd36vk4taq526js1azoek2m14qj18ij48u5lnxv9fpy44snwqc9iwm0aacskhc13rmf8nmpabyz4fne32a8a2vp8ridnd9gui2a0zih19y8ukyucnh9ke91fttg2xgae89tggspmgmasnkiizjc2le4unlpcnpglhnle89v1c9i7z6t7kfgzkdetkq86jwrz09rpwx0az44av9m5721a1j4nmlcz46mqwdnymnzki4gdkl15fhtfawqedz66h0bt8b79sra3wbxb9ie2zb6u88uk8nwj37plw28cyzwrkq3jykhl67djuug286jympwp9sel5c9cait3k54em47bklpyuy88k861j5iwgzsbv4zfoq0fhfzi6l7vc91l16c9l13ldpxno6ijfbdc4fk6gyumqsqw4samff58f4l59hic8yv5qh1guyegia38b2pm26j2klxfiqnh0a46do42ogc8b28b1xcdm2iiooc6v9aptfv687sj9arv6s1ucqmaw6cqaghxdgw1ic9pnybds2gw0wsvumokq5a2fezc2mpt3su03s5wl2ro6emor1z4otoybpfd8fn3kwj58osbgkpplwb52cs5d8sdelx4065h1dwhqipmyparoe8r4pw30cm1fzocu812z7culdf9hjljyl3v5fm4ob2fi13fj3r3e59j0yei97vqje15cbcidzmr4yztjjjx5l04z462bktj77yf0smvcr1h9lult8x5fv56chbthf5ihftff2rxe3vrld7bvyklk5kwg2j7uikb3znl1w0jq2iiqgpnuag0lz3ofkqgamqfougr7p2e68pfyzoeokl56g1w315u5yrgf0geq9xfjbg599e215kyixwto5ea6xifdvwhf9z7cd6jx676fqs9ewuwu2z4os52in173hml738i7pay3gy7i8yge8wyd8lm6eejw8al75hpzj32s5ry6hlgcwr

wall: 3

shelf: 2

volume: 08

page: 215

Footnotes

1. The author of this story remains unknown. Some scholars attribute it to the mysterious group called The Librarians, on which more is said later in this anthology.

2. This lecture used to introduce the Institute’s course History & Philosophy of Universal Libraries. Nothing else is known about this course.

3. This paper was encrypted as a location in the online Library of Babel and has been edited for legibility. It is thought to have been written by a former scholar of the Institute who left to pursue independent research on the Library. This mysterious scholar’s relationship with the First Librarian, a figure mentioned in the text, is subject to controversy (remember, the Library is a mischievous thing: it contains truths, half-truths, and plain lies). But we do know that this mysterious author survived the Great Collapse and still writes today—as do The Librarians.

4. The Librarian’s Code, the text around which Librarians formed, explores the philosophy and metaphysics behind Universal Libraries. It was authored by the mysterious First Librarian, whose identity is unknown but who is said to have been a scholar in the Institute for Humanity & The Library.

5. Some attribute to the First Librarian the other pieces of this anthology: the story of the old librarian, the lecture on universal libraries, and this very paper.

I would like to thank ‘Patient George’ for sharing his story in PSY100 during the lecture on Sensation & Perception, where I fainted and learned a lot about consciousness firsthand. That experience provided the grounds for this piece.

I would also like to thank Kurd Lasswitz and Jorge Luis Borges for writing about Universal Libraries and captivating my curious spirit. I guess they can’t read this now, but if the Other Side is indeed a large library that contains all literature that can ever be written, I’m sure they’ll find this acknowledgement somewhere in there.

Finally, I would like to thank Stephanie DaPonte for her willingness to listen to my obsessed monologues about Universal Libraries, and for all her support. You have helped me in numerous ways and I wish I could have done as much for you as you did for me. Your work is crucial in a society that struggles to understand religious experience, so don’t give up when faced with scepticism. It has never been easy to do what was most needed, for the patient neither sees the root cause of his symptoms nor likes the taste of medicine. You will help many.

I know I just said ‘finally’, but a sincere thanks also goes to the Noēsis team for the opportunity to publish this piece, as well as to its readers. I hope you find something awe-inspiring in this story.

Redlining, Racism, and Ethics in Visual Art

Madelyn Luther

Black artists throughout U.S. history have used visual, aural, written, and performance art as a method of resistance against instances of institutional racism. Redlining, a practice of housing discrimination that disenfranchised Black communities, has been explored by American visual artists of color such as Shanequa Benitez, Zora J. Murff, and Theaster Gates. These artists and others create their art as an act of resistance against white supremacy and to make a political statement about the pervasiveness of racism in American society and its effects on Black communities. The mere success of their work suggests that housing discrimination, over-policing, and institutional racism of all forms may serve to oppress Black Americans, but that these forms of racism will never erase Black Americans nor extinguish their creativity.

Redlining, Critical Race Theory, and Antiracism

Homeownership is a vital and effective way to build wealth in America. Black and Latinx families are statistically much less likely to own a house in America than their white counterparts (Elder et al., 2022). Therefore, the practice of redlining, which prevents Black and brown Americans from achieving upward economic mobility by forcing them into impoverished districts, acts as a barrier to gaining wealth. Robert Bullard, a professor of sociology and environmental injustice, defines redlining as a practice in which urban developers draw lines around Black and brown neighborhoods, categorizing them as hazardous or undesirable for loans. As such, these areas do not receive the same environmental, economic, and practical benefits as white communities (Bullard, 2023). While housing discrimination was made illegal by The Fair Housing Act of 1968, this did not mean that the practice ended then; in fact, the effects of housing discrimination endure to this day. Bullard also notes that Black and brown Americans face disproportionately higher health concerns, statistics that can be linked to the environment that they live in (2023). As such, the practice of redlining is directly linked not only to poverty among Black Americans but also to poorer health and as such can be understood as a public health crisis.

A theoretical framework and methodology that accepts that racism is ingrained in many parts of our society, including but not limited to the legal system and various social institutions, is critical race theory. One of the preeminent scholars in this area is Kimberlé Crenshaw, a civil rights advocate and law professor. Crenshaw argues that there are two forms of subordination on the basis of race: symbolic and material (Crenshaw, 1988, p. 1377). Housing discrimination falls into the material category. Practices of material subordination exclude Black Americans from certain privileges granted to white Americans and economically disadvantage them. She further notes that the American legal system too often feigns race neutrality and makes it as if racism is a thing of the past (Crenshaw, 1988, p. 1378). A clear example of enduring institutional racism is housing discrimination, which Shanequa Benitez, Zora J. Murff, and Theaster Gates explore in their various types of visual art.

Furthermore, scholar Ibram X. Kendi is one of the leading scholars on antiracism, an ideology present in the works of these three artists. To Kendi, there are only two ways of being in our world: racist and antiracist. He rejects the idea that one can be “not racist” or “color blind” and asserts that “there is no neutrality in the racial struggle” (Kendi, 2019, p. 19). He argues that racism is something instilled by societal norms and must be unlearned. An Aristotelian virtue ethicist lens can be applied to viewing racism not as a spectrum but instead as two distinct ways of being. Hence, racism is a vice, and antiracism is a virtue. Aristotle maintains that virtues can be learned and worked towards (Aristotle, p. 143). In the same sense, Kendi also argues that antiracism is not a fixed state of being but a mindset that can (and should) be constantly improved. Further, Aristotlean virtue ethicists posit that a virtuous person must do good actions because they have a good character, not because the act is intrinsically good. Kendi would argue that the antiracist person must practice antiracism not solely because it is good in itself, but also because they seek to become a more ethical person. Benitez, Murff, and Gates convey themes of racism and Black struggle in their pieces. They grapple with the hardships endured by institutional racism and how to resist and exist despite them. Their art conveys the trauma inflicted upon Black and brown communities and challenges viewers to act.

Artwork

Shanequa Benitez’s work was shown in a converted gallery space at YOHO Studios in Yonkers from February through April of 2023. Benitez is a local New York-based artist with the nonprofit Yonkers Arts and the Municipal Housing Authority for the City of Yonkers (Cuevas, 2023). Through mixed media, her work captures the remnants of redlining in Black communities. Two pieces from the exhibition in particular are worthy of note.

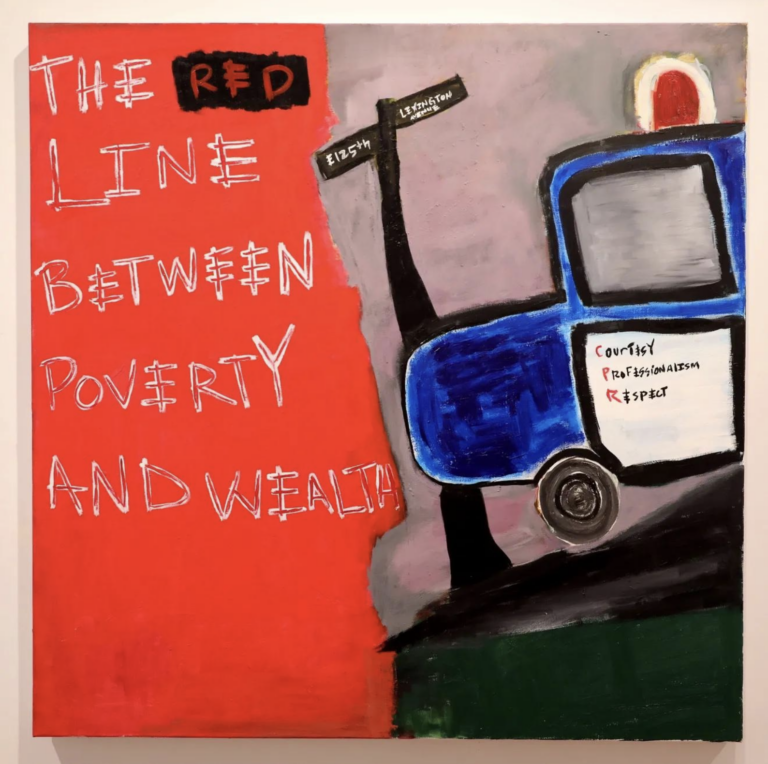

Firstly, “Redlining” portrays a police car with the words “COURTESY PROFESSIONALISM RESPECT” on the side and a street sign with the labels E 125th and Lexington Ave in Yonkers, NYC, NY. It contains the words “THE RED LINE BETWEEN POVERTY AND WEALTH.” These depictions suggest that this street intersection is the literal and metaphorical line between poverty and wealth. The practice of redlining physically designates Black communities into separate geographical areas, resulting in the divestment of these communities by governments and ethnically concentrated levels of poverty (Elder et al., 2022). The image of the police car alludes to the over-policing of marginalized communities. The words on the car highlight the irony that law enforcement officers are supposed to practice certain virtues; however, instances of police brutality and unjust treatment under the law suggest that law enforcement is systemically flawed. The art style and bright colors are jarring, which is intentional by Benitez, underscoring the sheer brutality that Black communities face at the hands of the police.

Secondly, “My Brother’s Keeper (Housing Court)” depicts a bus stop and, to the right, a building with the label “HOUSING COURT.” Two figures that look like young Black boys stand in the foreground, and the words “THE MASTERS TOOLS WILL NEVER DISMANTLE THE MASTERS HOUSE” are written above the building at the top of the image. Again, the art style and vivid colors are jarring, calling attention to the unjust nature of housing discrimination, racism, and wealth inequality.

Importantly, this piece alludes to Audre Lorde’s infamous speech “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1979). Though this speech was originally given orally at a feminist conference, it was also recorded in print in the 1981 feminist anthology book “This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color.” In this speech, Lorde argues that the tools of a racist patriarchy “may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change” (1981, p. 27). One of the tools in question is racism. Feminism cannot truly succeed without antiracism, and Lorde argues that feminists of her time do not adequately embrace this sentiment. Racism is a tool used to disenfranchise Black communities via practices like redlining that uphold white supremacy. Further, both Benitez and Lorde would likely agree that the struggles of all marginalized groups are interconnected, and many of these struggles originate from the systems of capitalism and colonialism. As such, Benitez’s piece can be interpreted to convey that small-scale reform does not do enough for Black communities. Instead, certain systems must be abolished to bring about genuine and necessary change.

The phrase “my brother’s keeper” in the piece’s title is likely a reference to the biblical idea that one is morally responsible for the well-being of a sibling or other human beings in general. The phrase at hand is perhaps most well-known as part of the story of Cain and Abel from the book of Genesis 4:9. The full title, “My Brother’s Keeper (Housing Court),” suggests that housing discrimination, redlining, poverty, and unequal treatment under the law create barriers to housing for Black and brown communities. Housing is a wealth-building tool, a protective structure, and a source of belonging. It is a structure to keep one’s ‘brothers’ sheltered from the outside world. While the government could provide increased infrastructure and support to impoverished communities, it instead allows banks and landlords to punish their tenants for not being able to afford rent prices, as is depicted in Benitez’s piece. Her work suggests that this practice is unjust and that landlords are immoral in their act of disenfranchising Black communities instead of treating others with equality and empathy.

Narrative ethics is a branch of ethics that focuses on identity through stories that explore ethical issues. Many narratives from religious texts explore ethical ideas in this way. Stories from the Christian Bible help form the core beliefs of the religion, as noted by professor of ethics Robert Roberts (2012). The Bible outlines certain virtues and vices, such as the vice Cain committed by slaying his brother. According to the Pew Research Center, the majority of Black Americans are Christian, and many within that majority are highly religious (Mohamed et al., 2021). Religion has historically been important to Black Americans, and perhaps the most well-known Christian civil rights advocate was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, who wrote his “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” while being imprisoned for participating in a nonviolent antiracist demonstration in 1963. In the letter, King cites scripture and urges readers to disobey unjust laws like segregation ordinances because they do not adhere to “the moral law or the law of God” (King, 1963, p. 457). Benitez draws on Christian narrative ethics, which King’s works are fundamental writings for in the context of social justice, through the title of her piece. She is encouraging viewers to empathize with disadvantaged communities and take action to support them.

Zora J. Murff is a renowned artist, educator, activist, and professor. His series At No Point In Between centers around redlining, police violence, and racism in Omaha, Nebraska. Murff states during an interview with LensCulture about the series that there are two types of violence inflicted upon the Black community: fast violence and slow violence. Murff cites this idea as originating from sociologist Rob Nixon in his book “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.” An example of slow violence is redlining—it is a type of violence that is not easily seen but rather manifests over time. An example of fast violence is an isolated instance of police brutality because the injustice of the act is understood more easily and its harm is immediate (Murff, 2018). At No Point In Between explores these two temporal forms of violence and how photography implicates them.

Fast violence is portrayed in the series by images of police officers and lynchings. “Implement” is one image from the series that depicts a group of officers being sworn into duty. Murff states that it “represents an institutional power structure, but also touches on resulting narratives created around police killings” (Murff, 2018). The image is chilling when situated in the series. Most of the police officers in the image are white and appear intimidating. Murff juxtaposes this image next to images like a Polaroid of a young Black man wearing a graduation cap and gown and a Black woman closing her eyes. This contrast shows how ingrained police violence and racism are in Black communities—these practices are a frequent occurrence, as common as a high school graduation.

Another image in this series is titled “Construct.” It is a black-and-white image taken from a bird’s eye view of the city of Omaha. Its title suggests that the construction of roads, highways, and other physical structures that physically separate communities is intentional. They are constructed to reinforce redlining, which in turn upholds white supremacy. At No Point In Between connects Black bodies and communities to their environment, geography, and history. It also resists the institution of white supremacy. Murff’s series, when considered holistically, does not just depict instances of violence alone. It also highlights the inherent joy and beauty in Black people, communities, and culture. The series celebrates small moments despite the many barriers that people of color face in Omaha and, in this way, resists the racist institutions that do not wish to see joy in Black Americans.

Police violence is inextricably tied to housing discrimination. In America, Black and brown people have been historically forced into poorer communities with higher rates of crime and increased police surveillance. According to the NAACP, “a Black person is five times more likely to be stopped without just cause than a white person,” and they are also incarcerated at higher rates than white Americans, especially for minor drug offenses (2023). The systems of housing discrimination and a racist justice system go hand in hand. These institutions uphold white supremacy, as Kimberlé Crenshaw also outlines in “Race, Reform, and Retrenchment: Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law” in 1988. The work of artists like Murff and Benitez depicts these institutions and their economic and psychological effects on Black communities. Their work uses pathetic messaging to call on viewers’ consciousnesses to acknowledge the injustices that Black Americans face and be antiracist. One artist whose work not only highlights housing discrimination but also gives back to their community is Theaster Gates.

Theaster Gates is a Chicago native and creative. He is perhaps most well-known for his large-scale urban installations that preserve and reinvest in spaces left behind (Gates, 2019). His Dorchester Projects are community-based, participatory, and archival. Gates purchases vacant and unmaintained properties on Dorchester Street in the South Side of Chicago and renovates them as part of his artwork. According to New York Times writer Ben Austen, these properties include an old bank that was shuttered for 33 years, a former Anheuser-Busch distribution warehouse, and others. Gates repurposes the materials from these vacant properties and either makes art out of them and sells them or uses them in the construction process. From the old bank, he sold the original marble, engraved, and carved, for thousands of dollars apiece (Austen 2013). The new spaces he creates function as art hubs and creative outlets for the community.

For example, one renovated building became the Black Cinema House, which hosts movie screenings and film club meetings (Austen, 2013). It acts as a space for community members to gather and converse with one another, fostering an open and creative environment. While the buildings of the Dorchester Projects stand on their own as three-dimensional pieces of visual art with aesthetic value, Gates’ own history with the South Side and his commitment to community engagement add a personal element to these pieces. His Dorchester Projects are more than a sculpture at a museum that sits behind a glass enclosure decade after decade. Gates provides resources for the community to engage with various art forms and opportunities for artists to succeed. The Projects are a way for Gates to give back to the city he calls home.

His work is similar to that of Rick Lowe and several other African American artists’ 1993 Project Row Houses. Like Gates’, their work is based on the “German artist Joseph Beuys’s concept of social sculpture, the idea that a work of art could be a practical social action” (Austen, 2013). Gates asserts through his art that it is the responsibility of artists to speak out when faced with injustice and to do something to better the community impacted. This idea can be related to antiracism as an Aristotelian virtue. It is virtuous and moral for an artist with good moral character and whose work is concerned with racism to use their work to bring about positive change. Gates’ work functions as an act of resistance because his investment in a historically disenfranchised community counters the practices of redlining and housing discrimination that uphold white supremacy and segregation, and it celebrates Black culture and beauty.

Conclusion

In sum, the art of Shanequa Benitez, Zora J. Murff, and Theaster Gates operate as acts of resistance to racism and convey a moral message that it is the responsibility of viewers and all people to resist institutional racism, white supremacy, and segregation. Drawing on the theories of Crenshaw, Kendi, King, and others, artists Benitez, Murff, and Gates would all attest that racism is institutionalized and that antiracist activism is a virtuous deed. Their work challenges viewers and community members to think beyond the confines of polite subtleties and gradual change and instead be revolutionary in their fight for racial equality.

References

Aristotle. (2020). Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. In The ethical life: fundamental readings in ethics and moral problems (pp. 143–152). Oxford University Press.

Austen, B. (2013). Chicago’s Opportunity Artist. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/22/magazine/chicagos-opportunity-artist.html

Benitez, S. (2023a). My Brother’s Keeper (Housing Court) (Yonkers, New York City, New York, USA) [Multimedia]. YOHO Studios.

Benitez, S. (2023b). Redlining (Yonkers, New York City, New York, USA) [Multimedia]. YOHO Studios.

Bullard, R. D. (2023). The Father of Environmental Justice Exposes the Geography of Inequity (Y. Funes, Interviewer) [Interview]. In Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-father-of-environmental-justice-exposes-the-geography-of-inequity/

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VIII: the Fair Housing Act, VIII (1968).

Crenshaw, K. (1988). Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law. Harvard Law Review, 101(7), 1331–1387. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3871&context=faculty_scholarship

Cuevas, E. (2023). Redlining in paint: In new exhibit, artist shows effects of discrimination on her Yonkers neighborhood. Lohud; USA Today. https://www.lohud.com/story/news/local/westchester/yonkers/2023/03/03/exhibit-by-yonkers-artist-shows-effects-of-redlining-on-neighborhood/69934692007/

Elder, K., Lo, L., & Freemark, Y. (2022). Homeownership in Assessments of Fair Housing. https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Homeownership-in-Assessments-of-Fair-Housing.pdf

Gates, T. (n.d.). Dorchester Projects (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Participatory Architectural Design]. Dorchester Projects.

Kendi, I. X. (2023). How to be an antiracist. One World. (Original work published 2019). ISBN: 9780525509295

King James Bible. Genesis 4:9. (2023). King James Bible Online. https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/ (Original work published 1769)

King Jr., M. L. (2020). Letter from Birmingham City Jail. In The ethical life: fundamental readings in ethics and moral problems (pp. 451–462). Oxford University Press.

Lorde, A., Anzaldúa, G., & Moraga, C. (1981). This bridge called my back writings by radical women of color. Persephone Press.

Lowe, R. (1993). Project Row Houses (Houston’s Third Ward, Texas, USA) [Architecture]. Project Row Houses. https://projectrowhouses.org/

Mohamed, B., Cox, K., Diamant, J., & Gecewicz, C. (2021). Religious beliefs among Black Americans. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/religious-beliefs-among-black-americans/

Murff, Z. J. (2018a). At No Point In Between – Photographs by Zora Murff (L.-L. Haines-Wangda, Interviewer) [Interview]. In LensCulture. https://www.lensculture.com/articles/zora-murff-at-no-point-in-between#slideshow

Murff, Z. J. (2018b). Construct [Photography]. MoMA Online.

Murff, Z. J. (2018c). Implement [Photography]. MoMA Online. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/432

MoMA. (2020). Zora J Murff. The Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/432

NAACP. (2021). Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. NAACP. https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

Roberts, R. (2012). Narrative Ethics. Philosophy Compass, 7(3), 174–182.